Featured image: An artist’s depiction of kobolds. Source: Forgotten Realms Wiki

In ancient folklore, the kobold is a small, pointy-eared, goblin-like creature with a short-temper and a mischievous spirit. While generally described as well-intentioned, angering a kobold is said to be a dangerous mistake. They are described as spirits that dwell among the living, and can sometimes take the form of humans, elements, or animals, depending upon where they choose to make their home.

What is most intriguing about the kobolds is not only their persistence into modern folklore but the way in which they seem to transcend various provinces and faiths. Known in England as brownies, in France as gobelins, in Belgium as kabouters and so on, kobolds are still carefully considered and respected in Germanic culture. However, the kobold does not first come from Germany but rather Greece. Though there is much deliberation over the origin of the kobolds, it is believed that they descend from the ancient Greek kobaloi, sprite-like creatures often invoked by followers of the god Dionysus and rogues. Even then, they were known as pranksters and tricksters, who simultaneously aided the god Dionysus in his bacchant endeavors. But by the 13th century, the kobolds had been adopted by the German people, culminating in the final name kobold, the Germanic suffix –olt (eventually –old) signifying of the creatures' supernatural origin.

Kobolds are typically described as small, pointy-eared, goblin-like creatures. Image source: Wikipedia

There are three known factions of the kobolds, each task-oriented and initially well intentioned. The sightings of the kobolds are few and far between, in part because they are said to complete tasks invisibly. Nevertheless, numerous people over the centuries have claimed to have seen the kobold, allowing a general description of their physicality and demeanor to be drawn.

DiscoverHousehold deityHumanBrownie (folklore)Spirit The most well-known, well-circulated type of kobold in Germanic folklore is the domesticated helper, not unlike the English brownie or hobgoblin. In the past, this sect has been perceived as akin to the Roman idea of lares and penates, familial household deities of protection.

By choice, a household kobold picks a family with which to tie itself, and it offers its services in the dead of the night. By adding dirt to the family's milk jugs and saw dust to the otherwise clean living quarters, the kobold tests the master of the house to see if he understands and knows the service being offered. If the master is smart, he will leave the sawdust and drink the dirty milk, signaling to the kobold that he accepts its help and will treat it with respect by sharing a portion of his nightly supper. From then on, the kobold will serve the master's family until the last of his line dies off or it is otherwise insulted.

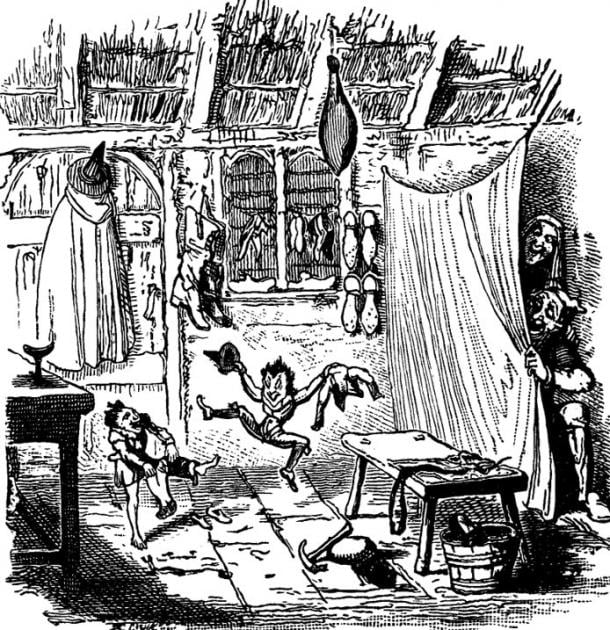

A kobold in the form of an infant helps with domestic chores. Image source: Wikipedia

However, tales of the dangers associated with insulting a kobold eventually led to the spirits being considered ill omens later in their mythology. One story, as written by folklorist Thomas Keightley, describes a kobold named Hödeken. Hödeken was insulted by a kitchen boy and the head cook refused to punish him. In the dead of the night, Hödeken beat the boy and tore him limb from limb, adding him to the pot of food cooking in the hearth. The cook was then killed for chastising the kobold's behavior. Instances like this are not uncommon in kobold culture, and thus have caused the other two sects of kobolds to be feared—more so than the household creatures, undoubtedly due to their rougher natures.

The second form of kobold, which came to be described in folklore in around the 1500s, is the crude and dirty miners. Akin to the Norse perception of dwarves, they are described as smaller than humans and hot tempered, and live underground to spend their days mining the metals of the earth. Though probably the least friendly of the kobolds, legends say that they are more interested in what they find than anything else, and are generally indifferent towards humans.

Nevertheless, stories of the mining kobolds were once so embedded within the human consciousness, that miners decided to name the ore ‘cobalt’ after them, because they blamed the kobold for the poisonous and troublesome nature of the typical arsenical ores of this metal, which polluted other mined elements.

Artist’s depiction of the mining kobolds. Credit: C. Cleveland

Finally, the third and least recognized type is the sea kobolds. These kobolds have been most often recorded by the people of northern Germany and the Netherlands, signifying that they may have been inspired by the previous two factions and lumped in with the kobolds due to physical and task similarities. Again, this group is similar to the household spirit, described as offering its protection and services to the captain and crew of a merchant or pirate ship.

These creatures have been recorded as helping prevent the ship they are on from sinking, however if the ship does sink, the kobold flees for its life, leaving the humans behind to fend for themselves. It is because of this that sighting of a kobold came to be seen as a bad omen; it was said that if a ship's captain sees one before leaving the dock, he is certainly better off remaining on land than tempting fate in the waters.

A sea kobold, from Buch Zur See, 1885. Image source: Wikipedia

That the kobolds traveled so far in both time and space shows the deep respect of their culture, and reveals further the inexplicable bond of the human consciousness.

References:

By Ryan Stone

- Brown, Robert. The Greek Dionysiak Myth, Part 2 (Kessinger Publishing, 2004.)

- "The Fairy Mythology: Germany: Kobolds." Sacred Texts. Accessed September 25, 2014.

- Grimm, Jacob. Teutonic Mythology, Part 2 (Kessinger Publishing, 2003).

- Keightley, Thomas. The Fairy Mythology, Illustrative of the Romance and Superstition of Various Countries (London: H. G. Bohn, 1850.)

- Liddell, Henry George, and Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones with the assistance of Roderick McKenzie (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940.)

- Rose, Carol. Spirits, Fairies, Leprechauns, and Goblins: An Encyclopedia (New York City: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc, 1996.)

- Snowe, Joseph. The Rhine, Legends Traditions, History, from Cologne to Mainz (London: F. C. Westley and J. Madden & Co., 1839).