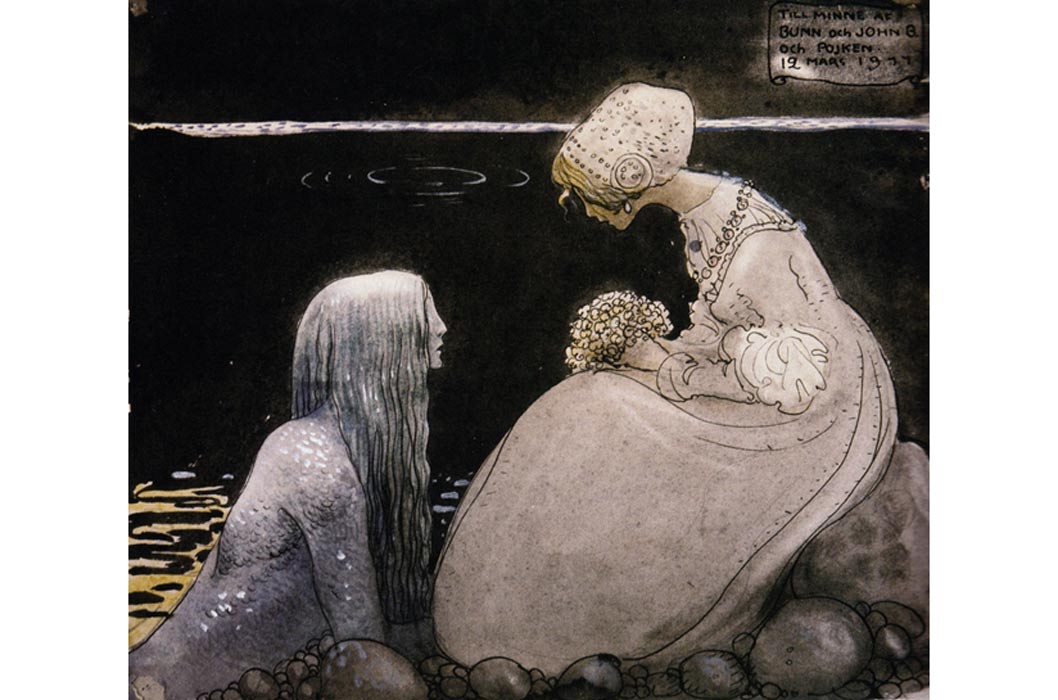

Top Image: “Agneta & the Sea King” by John Bauer. Source: Melusina MermaidFascination with the Danish ballad Agnete og Havmanden, or "Agnete and the Merman", has long been prominent in the Scandinavian countries. In spite of arguments over origin and dating, the poem has survived centuries of uncertainty through its thrilling themes of forbidden sexuality, spiritual toil, and outright abandonment.A Tragic Tale

Axel Olrik dates this ballad to the post-medieval period, though its precise origin date is uncertain. Olrik also believes that the source is German rather than the assumption that it is natively Danish. There were many variations of the ballad written during the 18th and 19th century which are considered the foundation for modern alterations. Among these texts, the ballads written by Jens Baggesen, Adam Gottlob Oehlenschläger, and Hans Christian Andersen are the most widely circulated.

In Jens Baggesen's rendition, c. 1812, the story is as follows: a beautiful young Danish woman, Agnete is approached by the unnamed merman while sitting near to the sea. The merman approaches her, professing his love, and she agrees to return to the sea with him admitting similar feelings. During her time under the sea, she bears the merman two children, but upon hearing the bells of the church from the surface, she begs her husband to allow her to go to the surface just one more time. Vowing to return the following day, the merman grants her request, and she leaves her children with her husband to return to the surface.

Coronation of the Sea Queen: "Now you shall be my queen & stay with me forever." Illustration by John Bauer. (Melusina Mermaid)

Yet the church does not provide the comfort Agnete hoped for. Approaching the church at midnight, Agnete finds herself confronted by her mother, who breaks the terrible news to her that the bells Agnete had heard were chimes signifying the funeral of Agnete's father, who had killed himself when the search for his daughter went unresolved. While begging her daughter to return to the surface, Agnete sees a tombstone beyond her mother—one which bears her mother's name. It is then Agnete realizes that her time in the sea was not equivalent to the time on land, and her entire family has died while she remained under the sea.DiscoverAxel OlrikDanish languageMermaidFairy taleAlterations to the Ballad

Adam Gottlob Oehlenschläger wrote a variation in the 19th century as well, with only a few minor changes. Agnete's name becomes Agnes, and Agnes has seven children rather than a mere two. Furthermore, it also discusses Agnes' death—absent from the original version—yet her death merely occurs after surfacing from the water.

Hans Christian Andersen wrote a version similar to Oehlenschläger's in 1832-4, made all the more intriguing to modern scholars by the inversion of gender roles in comparison to his earlier "The Little Mermaid," in which the mermaid fails to obtain her human true love and perishes at the end of the tale. Andersen's tale was performed at the Royal Theater in the 1840s, and it is likely because of his prominent name in fairy-tale circles that "Agnete and the Merman" remaining in circulation

Hans Christian Andersen in the garden of "Roligheden" near Copenhagen, Denmark. in 1869. (Public Domain)

In contrast to these Danish versions, an examination of a variation from Sweden will show the ways in which the tale altered depending on culture. A Swedish version keeps similar elements, however Agnete's love for the merman is falsified. In this ballad, Agnete refuses the merman's advances, offering him flowers instead, but is pulled beneath the waves and wiped of her human memories.

She then proceeds to marry the merman and produce seven children in eight years. It is only after—once again—hearing church bells that call her to resurface that she regains her memories and chooses to leave her underwater husband and children. When her husband comes for her, in an evident deus ex machina moment, God intervenes, banning the merman from entering the church and allowing Agnete to remain with her father.“Agneta, look at me,” he pleaded. But she did not raise her face. She kneeled on the spot as still as a statue. Illustration by John Bauer. (Melusina Mermaid)Christian Influences

Agnete's imaginary tale likely intrigued audiences during the 19th century, leading to these numerous variations because of the interaction between Christian and non-Christian forces. The merman, a magical being who finds place in the folklore and pre-Christian myths of numerous cultures, represents the pagan past of the Scandinavian lands, while the call of the church bells likely represents of the call of the Christian God.

In each tale, Agnete chooses to follow the bells above the surface, reuniting with her family. The Swedish version recounted here emphasizes this Christian-pre-Christian dichotomy, because the merman comes to the surface to reclaim his wife, but she ignores him to continue her prayers. It is after these prayers that she denounces him and her children, deciding to remain on the surface with her family and her Christian values. The extent to which this dichotomy is expressed differs depending on culture and author, but the Swedish variation is one of the most explicit. Yet with the continued utilization of church bells in other texts to call Agnete back to the shore, it is likely this was a consistent intention throughout the alterations.

“Agnete og Havmanden” (c. 1862) by Vilhelm Kyhn. (Public Domain)A Famous Statue

Another fascinating aspect of the story of Agnete and the Merman is that it is the subject of a unique sculpture created by Suste Bonnén c. 1992. At the base of the Slotshom Channel in Copenhagen one can see an underwater arrangement of Agnete and the Merman that is lit throughout the night and day. Though the ballad is not definitively proven to have come from a German or Danish source, the Danes evidently feel the story is an innate part of their culture, and the dedication to such an intriguing statue only emphasizes its value. Unlike the tale itself, these sculptures remain under the sea, never to return to the surface, likely serving a similar reminder of the pre-Christian and Christian dichotomy that once shook up the country.

Detail of the Agnete and the Merman sculpture. (Martin Macnaughton/Undervandsitetet)By Ryan Stone

References

- Anderson, Poul. 2011. The Merman's Children. Hachette: United Kingdom.

- Bassett, Fletcher S. 1885. "Legends and Superstitions of the Sea and of Sailors In all Lands and at all Times."

- Christensen, Dan. 2013. Hans Christian Ørsted: Reading Nature's Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kristensen, Evald Tang and Hakon Grüner-Nielsen. 1907. "Agnete and the Merman." Det Kongelige Bibliotek: Copenhagen. Accessed 20 July 2016.

- Morgensen, Soeren. 2014. "Adam. Gottlob Oehlenschläger." Project Runeberg. Accessed 21 July 2016.

- Oxenvad, Niels: "Henrik Hertz and Hans Christian Andersen", In: Johan de Mylius, Aage Jørgensen and Viggo Hjørnager Pedersen (ed.): Hans Christian Andersen. A Poet in Time. Papers from the Second International Hans Christian Andersen Conference 29 July to 2 August 1996. The Hans Christian Andersen Center, Odense University, Odense University Press: Odense, Denmark.

- Rossel, Sven Hakon. 1996. Hans Christian Andersen: Danish Writer and Citizen of the World. BRILL: Rodop

No comments :

Post a Comment